The Aesthetics of Agreement

Okuhle Madondo

June 10, 2025

It’s a scene familiar to anyone who has spent time in the digital town square: a comment section, a forum, a debate on social media. A lone voice offers a nuanced, evidence-based perspective. In response, they receive not counter-arguments, but a tidal wave of confident derision. The crowd, armed with memes, shared jargon, and a unified emotional tone, performs a consensus that has little to do with the facts at hand. The one who is right is made to feel foolish, while those who are wrong feel validated, powerful, and, most importantly, together. This frustrating spectacle is not a bug in our social code; it is a feature, a performance that reveals a profound human truth. In the theater of human interaction, we are often driven not by a dispassionate search for truth, but by a deeply ingrained evolutionary mandate to perform social cohesion. This leads us to prioritize the "aesthetics of correctness"—the signals, tones, and rituals that grant us favor with the crowd—over the often isolating and socially costly work of being factually right.

To understand why a person would sacrifice truth for acceptance, we must look not to the seminar room, but to the savanna. For our early human ancestors, social cohesion was not a matter of comfort but of survival. To be part of a group was to have access to shared resources, collective defense against predators, and mutual support. To be ostracized—cast out from the tribe—was a near-certain death sentence. An individual alone was an individual exposed, starved, or hunted.

In this high-stakes environment, the brain evolved a powerful cost-benefit analysis. What was more dangerous: being wrong about a fact (e.g., "I think those berries are safe to eat") or being wrong about the group's consensus (e.g., "The entire group is avoiding those berries")? The former might lead to a stomach ache; the latter could lead to exile and death. Our neurology was therefore sculpted to treat social isolation as an existential threat. Beliefs, in this context, became less about mapping reality and more about signaling loyalty. Adopting the tribe’s stories, its rituals, and its "truths" was the equivalent of wearing the team uniform. It was a loyalty pledge, a clear signal of "us" versus "them," and a vital insurance policy against the ultimate danger of being alone.

This ancient software still runs on our modern hardware. The evolutionary "why" manifests today as the psychological "how." The classic conformity experiments of the 1950s, conducted by Solomon Asch, famously demonstrated this. When faced with a group of actors all giving an obviously incorrect answer about the length of a line, a significant percentage of subjects would override the evidence of their own eyes and agree with the crowd.

This isn't simple cowardice; it's the result of two competing anxieties: the fear of being wrong (epistemic anxiety) and the fear of being alone (social anxiety). For most people, the latter is far more powerful and visceral. Psychologists distinguish between two types of social influence. Informational influence is when we conform because we believe the group is a source of accurate information. Normative influence, however, is when we conform to be liked, accepted, and to avoid social punishment. While both are at play, it is the normative pressure—the primal fear of ostracism—that drives us to agree even when we know the crowd is wrong. We aren't just seeking information; we are seeking sanctuary.

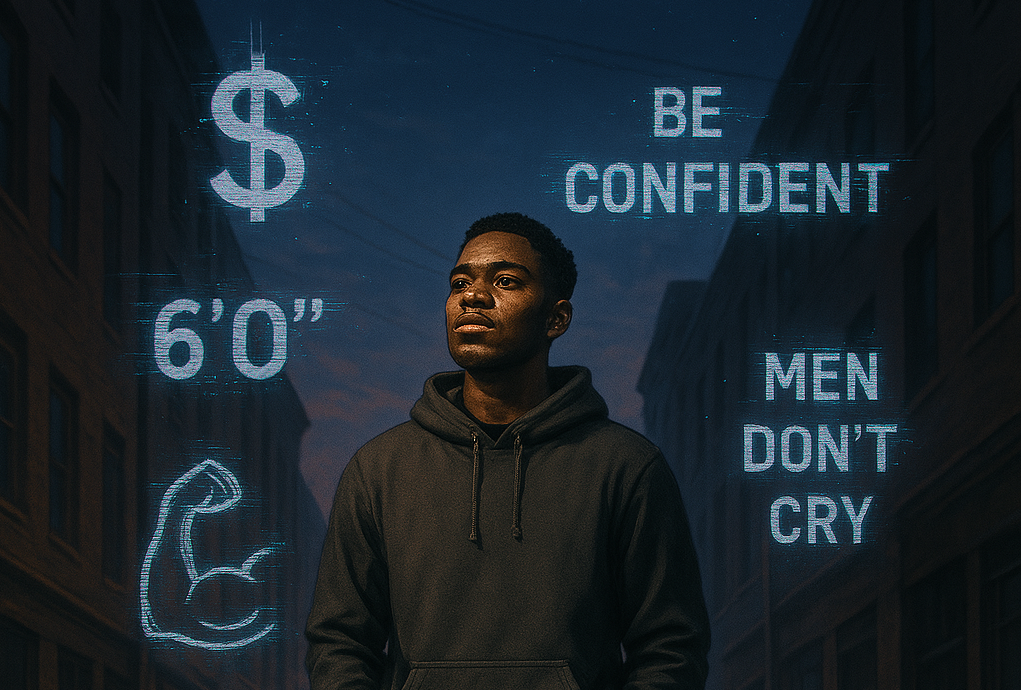

The modern drive for conformity is not just about silent agreement; it is a sophisticated and totalizing performance. This is nowhere more evident than on social media, where literally every visible action is, in some sense, a signal calibrated for tribal approval. Consider the construction of a social media identity. The choice of a profile photo is not merely about selecting a flattering image; it's a calculation. Does it project the right values—professionalism, activism, family-orientation, irreverent fun, maybe mystery? The username and bio are similarly strategic, often loaded with cultural references, political flags, or professional credentials designed to signal allegiance. Every post shared, every article liked, every photo album curated is another brick in the edifice of our public identity, meticulously designed to attract favor from our chosen in-group and demonstrate our fitness for membership.

This constant, low-grade performance is the essence of the "aesthetic of correctness." It’s a complex set of behaviors that go far beyond what we explicitly say, including:

-

Tone Policing: It’s often not what you say but how you say it. Adopting the correct emotional posture—be it righteous outrage, detached sarcasm, or solemn empathy—is paramount. Voicing a correct fact in the "wrong" tone can mark you as an outsider more quickly than voicing a wrong fact in the "right" tone.

-

The Lexicon of Belonging: Every in-group has its shibboleths—the jargon, buzzwords, and catchphrases that act as a password. In a corporate meeting, it might be "synergy" and "leveraging verticals." In an academic circle or online subculture, it could be terms like "problematic," "praxis," or "hegemony." Using the lexicon correctly proves you are one of the initiated.

-

Memeable Simplicity: Complex, nuanced truths are difficult to signal. They require long explanations and defy easy summary. Simple, emotionally charged slogans, however, are perfect identity markers. They are easily repeated, shared, and weaponized, functioning as a tribal chant that reinforces group identity far more effectively than a detailed white paper.

This performance is often what people mean when they decry "virtue signaling." It is the act of conspicuously donning the costume of a particular ideology to accrue social points, often with little regard for the substantive action or belief behind the display.

If our brain provides the script, the modern internet builds the stage, installs the lighting, and sells tickets. The digital age has supercharged this dynamic into a global coliseum of performative belief. Social media platforms provide frictionless conformity through likes, upvotes, and retweets—instant, low-cost ways to perform agreement and reap a small dopamine reward of social validation.

More insidiously, algorithms act as the coliseum’s directors. They don’t show us a representative sample of reality; they show us what is popular, what is emotionally engaging, and what our in-group already believes. This creates powerful echo chambers and feedback loops, manufacturing a consensus that feels overwhelming and unanimous, even if it’s an illusion. In this environment, the cost of dissent is higher than ever. Online pile-ons and "cancel culture" are the digital equivalents of tribal banishment. The fear is no longer just being disliked, but being de-platformed, doxxed, or losing one's livelihood—a modern form of exile that makes the pressure to conform immense.

The price for this performance of agreement is steep. On a personal level, it creates a world of anxiety for the would-be truth-teller, who must choose between their integrity and their social safety. It also creates a moral hollowness for the performer who, deep down, knows they are faking it.

Societally, the costs are catastrophic. In business and government, it leads to groupthink, where bad ideas go unchallenged because no one wants to be the lone dissenter. In science and academia, it leads to the stagnation of ideas, as researchers chase fashionable topics rather than risky but potentially revolutionary ones. And in public discourse, it fuels the social polarization that defines our era. We see competing aesthetics—entire worldviews distilled into a hat, a flag, or a profile picture—that are fundamentally about tribal identity, not policy or truth. We cease to have disagreements and instead engage in battles of belonging.

How, then, do we escape the theater? The solution is not to deny our social nature, but to cultivate epistemic courage—the willingness to prioritize truth even at a social cost.

On an individual level, this involves active self-awareness. It means pausing before joining a chorus to ask, "Do I believe this, or do I just want to belong?" It means practicing intellectual "steelmanning"—arguing the strongest possible case for the view you oppose—to break free from caricature. It requires normalizing the feeling of discomfort that comes with dissent and finding validation internally, rather than exclusively from the crowd.

Culturally and institutionally, we must create a new aesthetic: an aesthetic of curiosity. We must build norms that reward asking good questions more than having the "right" answers. Organizations can implement formal structures for safe dissent, like "Red Teams" that are tasked with challenging a plan, or "pre-mortems" where a team imagines a project has already failed and explains why. These tools create psychological safety, making it not only acceptable but valuable to be the one who speaks up.

We are, and always will be, caught in the tension between our ancient need for social approval and our modern need for objective truth. Our savanna brain, with its primal fear of exile, now navigates a digital world of algorithmic amplifiers and global social stakes. The result is the pervasive performance of agreement, an aesthetic that values the look of correctness over the substance of it.

But our evolutionary heritage need not be our master. By understanding the deep-seated instincts that drive us toward the comfort of the crowd, we gain the power to consciously choose a different path. The goal is not to become isolated truth-seekers, devoid of social connection. It is to build communities and a culture where dissent is not a threat, where curiosity is a virtue, and where we can find a profound and lasting beauty not in the seamlessness of our agreement, but in the courageous, messy, and essential pursuit of what is true.

Continue Reading

Agency

13 January 2025

There’s this story we tell ourselves in some corners of the world, about starting from nothing and building something real. It’s flawed, messy even, but you can’t deny it’s got a pull—people keep chasing it, generation after generation.